Sportident Primer

Sportident is a system commonly used for timing in e.g. the sport of orienteering. One part of the system is battery powered stations placed at the start, finish and control posts along the course. The other main part is small RFID “cards” the athletes carry with them. The cards store information, like time and code number, from the stations they come in contact with. At the end of a race, the data in the cards is read out and processed by some piece of software to create the results list.

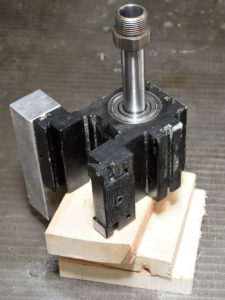

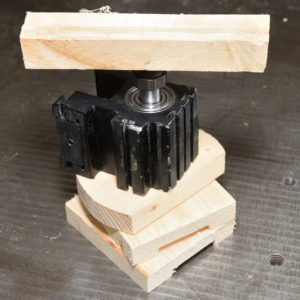

The stations come in different versions. The most common type (often used at control posts) has no other means of communication than the inductive RFID link, while others have e.g. a serial port (not sold anymore) or USB. The wire-free stations can be connected to a computer by inductively coupling them via a ferrite rod to a station connected to a computer.

There is non-volatile memory inside each station and this stores station configuration information, as well as a log of which cards have punched at the station and at what time.

Sportident provides a gratis program called Sportident Config+ that can manage the Sportident hardware, by e.g. upgrading firmware, setting operating mode, setting time, reading out backup memory, reading and configuring cards etc. While the program is generally quite complete in its functionality, it has a rather inefficient GUI for doing the same operation on many stations in a row, like setting up all stations to have synchronized clocks and the same operating time. Or reading out the backup memories of many stations. Such operations require a lot of clicking for each station and small mistakes can cause undesirable results.

Python Code

The communication protocol used over the USB/serial port is partially documented in a non-maintained document not generally available, although it is possible to get a copy of this document by asking Sportident for it. I found more information about the protocol and the configuration data of the stations in the source code of a program called sireader.py which I found on Github. This code was developed by Gaudenz Steinlin, Simon Harston and Jan Vorwerk in 2008-2015 and the purpose primarily seems to have been to read out the information of cards inserted into a station connected to a computer.

I wanted to do more than this however. First, I wanted to be able to read out the backup memory of many stations and store the information in separate CSV files with minimal user intervention for each station. Second, I wanted to have a streamlined way of preparing many stations for an event. This involves synchronizing the clocks, clearing the backup memory, setting the operating time (time before the station goes to sleep) and a few other settings.

Some of this was quite straightforward to do using the code in sireader.py, but some of it required more investigation of the communication protocol by means of a logic analyzer as well as the addition of several new methods in the main class of the code. I also had to study the raw configuration data of stations, which consists of 128 partially documented bytes, and compare it between stations in different modes to be able to get to the settings and information I wanted.

The result of all this is currently an extended version of the python code, which I call sireader2.py since it is not necessarily 100% compatible with sireader.py and it also contains a lot more functionality and documentation of a few more parts of the Sportident station configuration data.

I have also written scripts which use sireader2.py to do what I set out to do, namely to read backup memories and normalize station settings.

All of the code is freely available under GPL 3 at the following github repository: