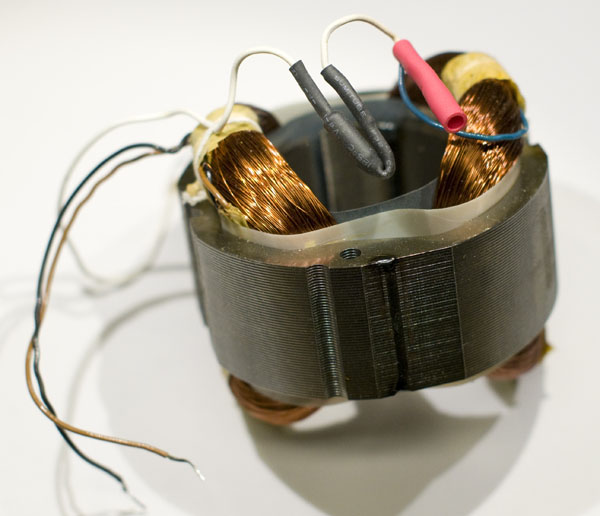

I recently had a duh moment. I was trying to repair a broken fan motor and I had determined that the immediate problem was that a thermal fuse used to protect the stator windings from overheating was broken. I ordered a few new thermal fuses, soldered one in and carefully insulated it electrically using heat shrink tubing.

When I tried to power up the fan, I was surprised to find that it was as dead as before. Some quick troubleshooting revealed that the new fuse was broken. Since the motor had not even made the tiniest jerk when I plugged it in, I assumed the fuse must strangely enough have been dead on arrival and I removed it from the motor.

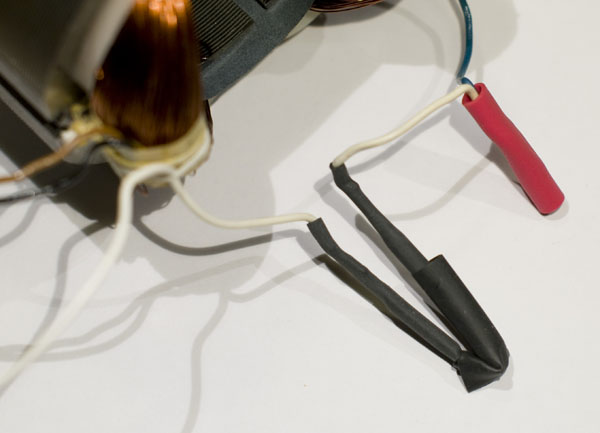

This is what the fuse looked like when I had removed it:

Fortunately, I had more fuses, so I proceeded to solder another one into the circuit. Wise from my previous experience, I verified that it was working before the operation and I also measured it after I had soldered and heat shrunk it into the motor circuit. To my surprise it was suddenly broken! And I had not even powered the motor up!

This is when the duh moment occurred.

Thermal fuses blow in an unresettable fashion when they reach a certain temperature, in my case around 120 °C. This is the whole point of the component. And I had failed to consider this when I happily soldered the thing in, just as if it were a resistor or some other normal component. There is obviously a big risk – not to say certainty – that both during soldering and while shrinking the tubes, the fuse gets heated to higher temperatures than it can stand.

So how do we get around this problem? I did not have any thermal fuses with long leads that would insulate them during soldering, but with some care it is in fact possible to solder a thermal fuse. Here are the tricks I used in my third attempt:

- Do not shorten the leads of the fuse. Leave them as long as they are.

- Put several alligator clips on the lead between the body of the fuse and the tip where you apply solder. This is to lead away heat so that it does not reach the body (see picture below).

- Solder for as short a duration of time as possible. Preferably less than a second at a time to prevent heating of larger parts of the lead. But be careful to not get a cold solder joint despite this. It’s a delicate balance.

- Do not shrink the tubes. Let them just sit there loosely.

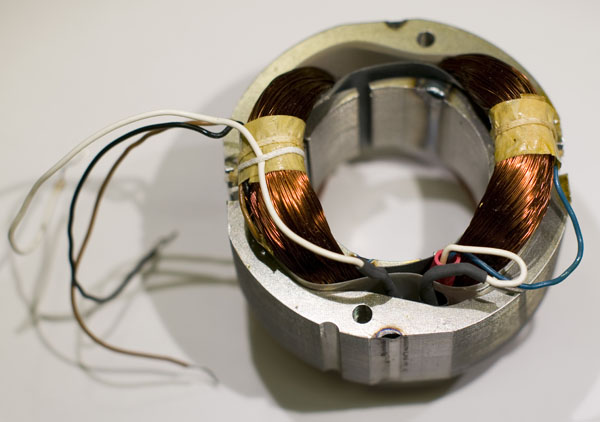

Below are some pictures from the process.

Using these tricks, my third attempt was successful and the fan is now back in working condition.

It cost me two thermal fuses, but I think I have got the lesson about what not to do to this (for me at least) somewhat unusual component.