|

|

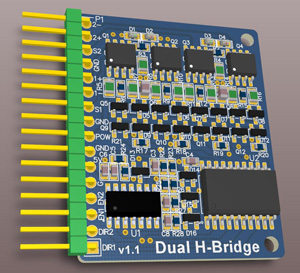

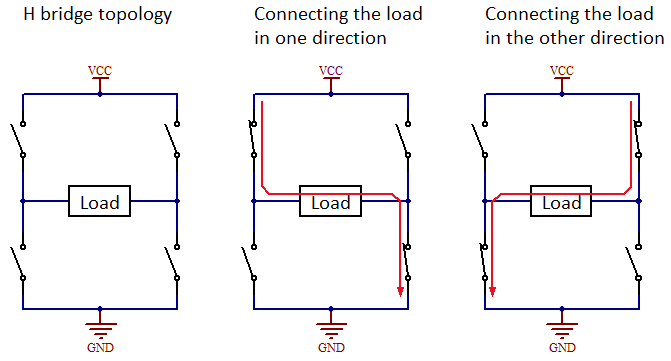

Design of an H BridgeDesign of an H bridgeAn "H bridge" is a circuit that can connect a supply voltage to a load in either direction. Typical usages of an H bridge are to drive a DC-motor forwards or backwards or to drive the windings of bipolar stepper motors. They find extensive use in robotics and other areas where motors or solenoids need to be controlled. Wikipedia has some more background information about H bridges, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H-bridge. Figure 1 below shows the basic topology of an H bridge. The reason for the name of the circuit should be obvious from the figure.

Figure 1. Topology and basic operation of an H bridge.

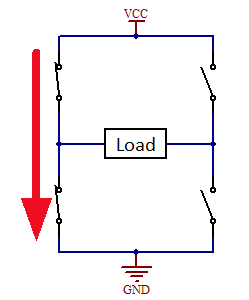

In practice the switches are usually implemented as some sort of transistors (bipolar, MOSFET or IGBT). The switches are closed diagonally (top left and lower right or top right and lower left) to connect the supply to the load in either direction. ChallengesThere are some challenges associated with H bridges. The two main ones are probably to avoid shoot-through and to drive the high side transistors. Shoot-through is the condition when either both of the left switches or both of the right switches are closed at the same time. This of course causes a short circuit which is a bad thing and can potentially destroy the switches or other components. Figure 2 illustrates the phenomenon. There are two plausible ways in which this can occur. One is that illegal control signals are applied, e.g. due to a software bug, and the other is that there is a short and unintentional overlap in the gate drive signals when switching from one polarity to the other.

Figure 2. The two left switches are accidentally on

at the same time causing a large short circuit current to flow.

The reason driving the high side transistors is a challenge is that they are referenced to a relatively high supply voltage instead of to ground while the control signals (typically coming from a micro controller or similar) are ground referenced. So some kind of level shifting circuitry is needed. Why build an H bridge?I had some odd 5-phase bipolar stepper motors (see separate article) lying around and just for fun I decided to design and build an H bridge that is suitable for driving these motors. A label on the motor says "Iw = 0.21 A, Rw = 32 ohms", so the H bridge needed to be able to support a drive voltage of 6.7 V. Factors that contributed to my decision to design and build an H bridge was that I had never done it before, I did not know beforehand exactly how to do it, the result would be at least a little interesting (a moving stepper motor) and it seemed like a reasonably small project that would be possible to complete with a limited amount of time and effort. Design choicesThe current of about 200 mA is not particularly high and it might be feasible to use bipolar transistors (BJTs) as switches. For higher currents, beefy power transistors with consequently lower current gain would have to be used and this would require a substantial base current, which can be a bit impractical to handle and cause a lot of loss and heat that needs to be dissipated. I decided to build the bridge with some margin on the current and voltage handling requirements and to use MOSFETs to avoid the problem of the power dissipation caused by the static base current of BJTs. NMOS transistors are about three times more efficient than PMOS transistors in terms of device size (cost) and gate capacitance for a given on-resistance, so for high-power designs it is advantageous to use NMOS transistors for both the upper and the lower switches. The problem with using NMOS transistors for the upper switches is however that they need a gate voltage that is higher than the bridge supply voltage. If PMOS transistors are used, gate voltages below the supply voltage are sufficient. For the convenience of avoiding an extra supply voltage and since the current is rather low and the cost of suitable PMOS transistors therefore not prohibitive, I decided to use PMOS transistors as the top switches and NMOS devices as the bottom ones. I wanted the design to be fail-safe in the sense that no combination or sequence of control signals could cause shoot-through so that bugs in the micro controller code would never be able to cause dangerous conditions. Two things are needed for this:

A conceptual solution that achieves the translation between the Enable/Direction control signals and the gate signals as well as introduces a delay when the transistors are about to turn on is shown in figure 3 below. Figure 3. Conceptual diagram of how the gate drive

signals of the H bridge are generated. (Click on image to enlarge.)

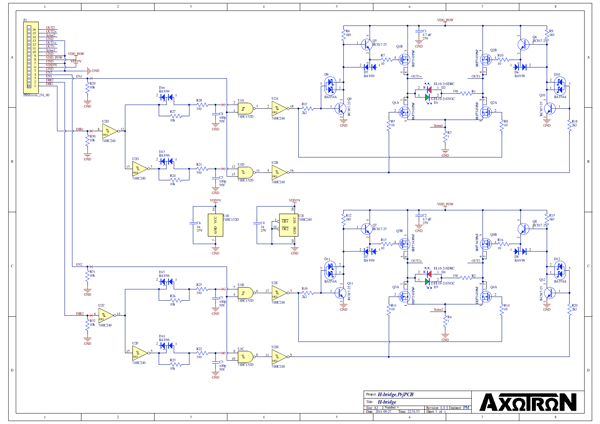

The two AND gates allow the enable signal to disconnect the control signals from the gates of the MOSFETs. The diode/resistor combinations make the charging of the capacitors slower than the discharging so that it takes longer for the gate drive signals to reach the transistors when the transistors are about to turn on than when they are about to turn off. By letting the gate control signals from the AND gates control the transistors diagonally, a level change from one of the AND gates always either turns on or turns off both transistors that are controlled by the gate. This makes it possible to control the timing of the four transistors with just two delay circuits. The inverters I2 and I3 need to convert the logic levels from the AND gates to voltages suitable for driving the top transistors. Detailed designThere are many details to fill in to complete the design. Figure 4 below shows the full schematic that resulted from the design process. It can be useful to refer back to it when reading the sections below on how it came together. Figure 4. Schematic diagram of complete (dual) H

bridge. (Click on image to enlarge.)

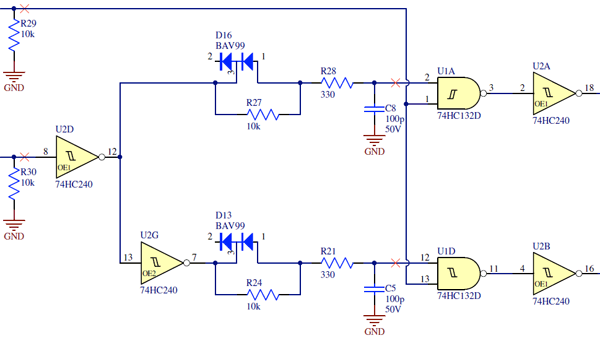

Choice of logic gatesThe AND gates of figure 3 need to have Schmitt trigger inputs since they are driven by relatively slowly changing voltages. Unfortunately there are no AND Schmitt triggers available. Schmitt trigger NOR gates could be an alternative since both NOR and AND gates have a low output signal when they are disabled. Using NOR gates would make the enable signal active low, but that is no drawback. An advantage with using NOR gates is that the inverter I1 could be implemented by a NOR gate and then a single logic IC would suffice for the H bridge. As it turns out there are no NOR Schmitt triggers available either, so we are forced to use NAND Schmitt triggers (which do in fact exist). This means that we need to invert the outputs of the gates and while that could be done with the two other NAND gates in the same package we still need to implement the inverter I1 and preferably also have another buffer at the input of the Direction signal so that the external control signal does not have to drive the RC-link (we cannot be sure of the analog properties of the external Direction signal and we do not want the operation of the H bridge to be highly dependent upon the analog properties of a controlling signal. So we seem to need two logic ICs for the H bridge to give us the required two NAND gates and four inverters. There are however octal inverters available in the '240 series of logic circuits and together with a '32 quad NAND gate we have enough gates for two bridges. This is the reason I decided to build two bridges on the same board. Figure 5 below shows the resulting design. Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the logic gates and

asymmetrical timing circuitry. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Several different logic families could have been used, but I wanted NAND gates that have CMOS input levels since that means that the Schmitt trigger inputs will switch at about half the supply voltage and I also want the inverters to have CMOS outputs to drive the gates of the NFETs up to about 5 V. So the NAND gates could be e.g. of the HC or AC families, whereas the inverters could be HC, HCT or AC etc. I decided to use HC for both. Using HCT for the inverter to also accommodate TTL levels on the Direction signal would not be a an advantage since the Enable signal does anyway have to have CMOS levels. Other input stage choicesI put pull-down resistors on the input signals to keep them at valid and safe (off) logic levels in case some input should at some time be left unconnected. CMOS inputs have very high impedance and can otherwise easily pick up noise that could cause a connected motor to go crazy. And it is generally good design practice to make modules robust anyway. I chose BAV99 for the diodes as this is an inexpensive diode I often use. In fact, BAV99 cnosists of two diodes in a SOT23 package so it may seem wasteful to buy two diodes and use only one of them. But instead of introducing another diode in the component library I decided to stick with an old and inexpensive one that I also happened to have in stock. To limit the current surge when the capacitors are to be charged, I put an extra 330 ohm resistor in series with the diode/resistor pair. The values of the other resistor and the capacitor were first approximately determined by hand calculation, then simulated using LTSpice and then fine tuned after the circuit had been built to make sure there is no shoot-through and a little margin. High side driverI found some inspiration in designing the H bridge in the following document from Texas Instruments:

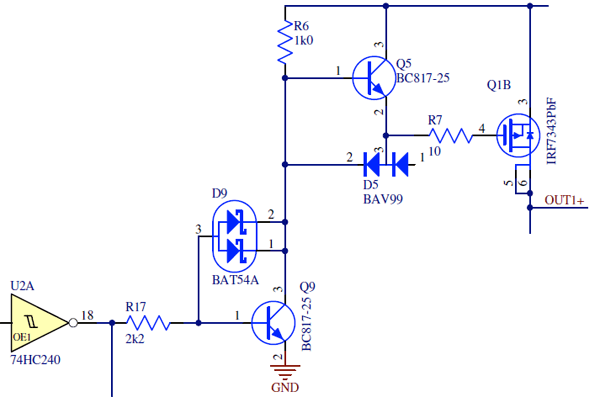

None of the circuits in that document did however fit the bill perfectly for this project and I had to develop something else, partly based on ideas in the document. The driver circuit for the high side PMOS transistor needs to invert the signal and increase the swing to the supply voltage of the motor, which may be at least 7 V. It has to be able to charge and discharge the gate capacitance of the FET relatively quickly and pull it high with a low impedance when it is supposed to do so, so that the PFET stays off even though the parasitic gate-drain capacitance will act to pull it low when the lower NMOS transistor turns on and quickly pulls the drain voltage down. Figure 6. Schematic diagram of the high side driver.

(Click on image to enlarge.)

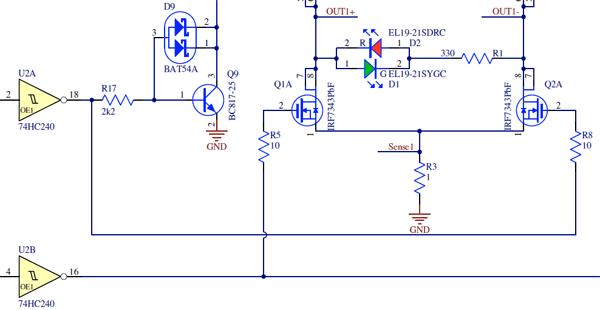

Figure 6 shows the finished driver circuit. The inversion and level shifting is handled by the NPN transistor Q9. This transistor would be very slow to turn off since it would be in saturation if it were not for the Schottky diode(s) from base to collector that prevents it from saturating. This is the same technique used internally in LSTTL logic to speed up the switching. I happened to have used the diode BAT54A before and decided to use it again. This is a dual diode and I put both diodes in parallel. Q5 is connected as an emitter follower and acts to provide the required low impedance to the supply rail when the PMOS transistor shall be off. Just relying on R6 to pull the gate high would have increased the time to pull the gate high (i.e. to turn off the transistor) substantially, but more importantly, the resistor would not have been able to keep the gate high when there is a quick drop (large negative dV/dt) at the drain of the PMOS transistor as a result of the lower NMOS turning on. The diode D5 provides a path for pulling the gate low when the PMOS is to turn on. A PNP emitter follower could have been used here to speed up the turn-on a bit, but we do intentionally slow down the turn-on anyway and the diode solution is fast enough. A small gate resistor R7 limits gate current surges and reduces the risk of ringing in the gate circuit. The rest of the circuitFigure 7 shows some other details of the bridge circuit. Figure 7. Schematic of the low side driver and some

other details. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Driving the NMOS transistor is much simpler. A plain gate resistor (R8) is connected between the output of the inverter and the gate. I added a current sense resistor in the source leads of the NMOS transistors to be able to conveniently measure the current and verify that there is no shoot-through taking place. 1 ohm was selected as a compromise between getting a decent voltage to be measured by an oscilloscope and minimizing loss. At 0.2 A, we get 0.2 V drop and this is relatively insignificant compared to a supply voltage of 6 or 7 V. When the testing has been completed the 1-ohm resistor can be replaced by a 0-ohm resistor. For MOSFETs I selected IRF7343 which is an NMOS/PMOS combination in a single SO8 package. This selection was a compromise between price, availability and on-resistance. The maximum current the transistors support is much higher than what is required in this application, so if low cost were the main design goal; some other transistors would have been a better choice. Like most (all?) power MOSFETs, these transistors contain integral bulk diodes that are very useful in this application since they will take care of the current to discharge the motor winding when the bridge turns off. If bipolars had been used instead of MOSFETs, such diodes would have been necessary to add as discrete components to prevent damage to the transistors. I also added LEDs across the H bridge output. This gives a convenient visual indication of what the circuit is up to and can be very useful during development of any device making use of the bridge. For a finished product the LEDs might be better left out. I decided to put the dual H bridge circuit on a double sided PCB and pull out all the external signals to a one-row pin header, instead of designing a complete board with H bridge, micro controller, power supply etc. This minimized the effort required to finish the H bridge part of the project and it is always possible to integrate the H bridge together with more circuitry on a future board if that would become necessary. © Per Magnusson, Axotron |

| Updated: 2016-12-11, 14:28:18 |

|

![[SW flag]](pic/Sw_flag_40.png)

![[UK/US flag]](pic/UK-US_flag_40.png)

![[PDF]](articles/H-Bridge/resources/pdf.png) The schematic as a PDF

The schematic as a PDF